Let’s just get this out of the way: this post is coming out two days later than I promised, and that’s because my son’s school was closed for two days for weather. He was largely uninterested in helping me write a post about John Irving (the closest we got was me describing the plot of the book to him and him saying “okay" before going back to reading Fudge-a-Mania, an altogether much less graphic book).

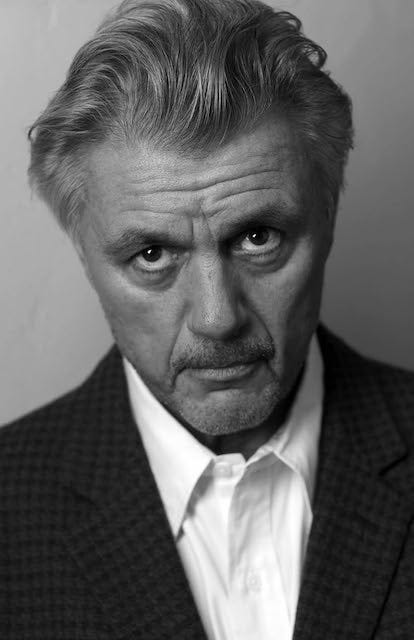

But we’re here now, so let’s get into it. As you hopefully know, this newsletter isn’t really a place where we get into history or cultural significance—there are people who do that far better than I could, and I’m not a professor. The vibes here are more “humorous recap with lots of personal details,” but I do still want to give you the tiniest bit of background on John Irving, in case you aren’t familiar with the man at all. First off, he looks like this.

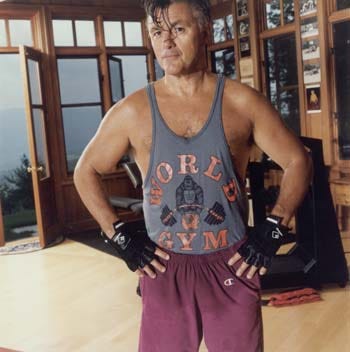

And sometimes, he looks like this, because he is (was?) a wrestler. He’s now 82 and I’m going to assume he’s not wrestling at this age.

The biography on the back of my paperback copy of The Cider House Rules tells you that he’s been nominated for a National Book Award three times (and won for The World According to Garp), that he won an Oscar in 2000 for best adapted screenplay (for the film version of the very book we’re now discussing), and that he was inducted into the National Wrestling Hall of Fame in 1992. In short, the man has range.

John Irving has, as long as I can remember, seemed like one of the Main Guys for me. In my leisure reading in high school, I almost exclusively read men (female novelists hated to see me coming, because I was going to ignore their entire body of work) and John Irving was one of the biggies. The World According to Garp blew my teenage mind and continues to live rent-free in my head, despite me trying to forcibly evict several sex scenes (they’re claiming squatter’s rights because that brain space has long been abandoned). A Prayer for Owen Meany felt life-changing at the time, although I couldn’t really tell you why now—clearly I’m due for a re-read. By the time I was in college, he was still publishing his doorstop novels regularly, although I stopped reading them, for whatever reason. I’ve mentioned this here before, but I think a lot about the guy in my senior year September 11th Literature seminar who (seemingly unprompted?) told us all that the three greatest living American writers were John Updike, Philip Roth, and John Irving. And now John Irving is the only one who’s still living! David Lynch’s death last week really shook me and made me realize that my Main Guys are all really old, and although the great thing about writing is that you can still produce great (perhaps even your best) work late in life, you can’t really outrun mortality. Jonathan Franzen, please give us that Crossroads sequel sooner rather than later.

And speaking of our boy J. Franz…one thing he and John Irving have in common in their love of a Big Novel. And not just length, although also length (my copy of The Cider House Rules clocks in at 602 pages, not counting the backmatter). They’re both writing novels on a huge canvas with many characters that take place across a large swath of time. I recently listened to a 2016 episode of the podcast What It Takes1, and he discussed his love of 19th century novels, like Dickens. He’s wholly uninterested in Hemingway, Faulkner, etc. (it goes without saying that he probably doesn’t care for most of what’s going on in literature at the moment). He writes books with big characters, and many characters, but he’s also writing books with a lot of plot. No one could pick up this book and say nothing’s happening.

And oh, what’s happening. You guys, it’s a lot. I will say that when I chose this book to read and discuss here, I wasn’t necessarily thinking about how timely it would be and I also wasn’t thinking about how graphic it would be. Well, we’re here now. There’s no turning back!

The Cider House Rules came out in 1985, a mere year before I burst onto the scene (/was born). We bounce around in time a little throughout our main characters’ lives, but the novel begins in the 1920s—adding to that old-fashioned feeling, all years are written as, for example, “192_”). Dr. Wilbur Larch runs a combination orphanage/ abortion clinic where he’s helped by the literal best nurses in the world, Nurse Edna and Nurse Angela. They’re in charge of naming the babies, and Nurse Edna, who is in love with Dr. Larch, calls them all some variation of his name (a lot of Wilburs). Nurse Angela is so over Edna’s crush and names all her babies “from a family history of many dead but cherished pets (Felix, Fuzzy, Smoky, Sam, Snowy, Curly, Ed and so forth.” She will not name a boy Bandit because that seems like a girl’s name to her.

If Jonathan Franzen has an obsession with poop (and he does), John Irving has an obsession, in this book, with the phase “little penis.” It’s in the first line and so far, in these first 223 pages, it shows no signs of letting up. I guess there’s no getting around it when you’re dealing with so many babies.

Dr. Larch is a man who has a lot of trauma in his past—family trauma, sure, but also the fact that he got a, frankly, horrifying case of gonorrhea from the one and only time he had sex, with a sex worker his father hired for him. Because of this terrible experience, he decides he’s never going to have sex again. Instead, his vice is a raging ether addiction. Not to be like “men will literally dedicate their lives to providing safe abortions instead of going to therapy” but…

Larch gets into the world of obstetrics but quickly realizes that women are dying because of back-alley abortions. It takes him exactly one visit to a horrible, secretive abortion provider before he decides to take matters into his own hands—he sees a very young girl, pregnant by her own father, and decides that he’s going to give her an abortion to save her from this dangerous place that’s killing women. An an obstetrician, he knows what to do and how to be safe. And after that, he’s basically off to the races, eventually opening an orphanage, St. Cloud’s, in Maine that provides “one abortion for every three births. Over the years, it would go to one in four, then to one in five.”

There’s a lot in this book so far that I’ve found profoundly moving (and so many times I’ve thought, “why haven’t I read this yet??”), but I found this distillation of Larch’s philosophy particularly great:

“He was an obstetrician; he delivered babies into the world. His colleagues called this ‘the Lord’s work.’ And he was an abortionist; he delivered mothers, too. His colleagues called this ‘the Devil’s work,’ but it was all the Lord’s work to Wilbur Larch…He would deliver babies. He would deliver mothers, too.”

Dr. Larch sees for himself the situations these women are in—the sex workers who cannot care for a baby and are willing to drink poison if they can’t procure an abortion. The children who are victims of incest. All of the women who are willing to take desperate measures, measures that very well may result in their own deaths, and he wants to do something about it for the simple reason that he can. He has the training and he doesn’t see himself as any better than they are.

But Dr. Larch has one problem. Not orphans, and not abortions (Dr. Larch says “it is not a problem that every woman who gets pregnant doesn’t necessarily want her baby; perhaps we can look ahead to a more enlightened time, when women will have the right to abort the birth of an unwanted child”—well, Dr. Larch, I guess we’ll keep looking ahead!). His problem is an orphan named Homer Wells: “We have managed to make the orphanage his home, and that is the problem.”

Homer Wells simply will not be adopted because he loves the orphanage too much. He’s at home there! Families try and fail to adopt him four times, the last time being the craziest—an outdoorsy couple takes him camping and then they get swept away by a log drive. Irving casually reports their deaths almost as an afterthought: “The Ramses Paper Company wouldn’t recover Billy and Grant’s bodies for three days; they found them nearly four miles away.” For all the true tragedies and grisly deaths in this book, it’s worth mentioning that there’s some almost slapstick comedy thrown in there as well. All due respect to Billy and Grant (RIP) but no one seems to be all that torn up about their deaths.

And so Homer Wells stays at St. Cloud’s, the oldest orphan there, and helps Dr. Larch, who “realized that this was also the Lord’s work: teaching Homer Wells, telling him everything, making sure he learned right from wrong. It was a lot of work, the Lord’s work, but if one was going to be presumptuous enough to undertake it, one had to do it perfectly.”

Just…hold on a moment, I’ve got something in my eye.

I’m sorry to bring up my Midlife Philosophical Crisis, but I keep thinking that Dr. Larch is displaying a lot of Stoic attributes. In many ways, he’s not unlike Paul Giamatti in The Holdovers.

Homer wants nothing more than to “be of use,” and he feels that the place he can best do that is St. Cloud’s. Dr. Larch puts him to work, not just at learning obstetrics but also reading to the orphans. Here’s where John Irving’s love of the 19th century novels really comes through: he reads David Copperfield and Great Expectations to the boys and Jane Eyre to the girls. Are you sensing a theme here? They’re all orphan novels! At first I found this hilariously bleak, but then I kind of got it—I mean, maybe it’s more depressing to read the orphans books about happy family lives. Now they’re reading about spunky orphans with a get-up-and-go spirit (by which I mean now they’re reading about the nonstop tragedy and turmoil Jane Eyre goes through).

Homer even takes to using a passage from David Copperfield as his own personal mantra: “Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show.”

It’s also worth noting that this is where Dr. Larch utters his famous line, “Good night—you Princes of Maine, you Kings of New England!” to the orphans, because “here in St. Cloud’s, we treat orphans as if they came from royal families.”

This is a plot-dense book, so there are far too many things happening for me to mention them all in this newsletter. But here are a few:

-There’s a character named Melony, the oldest not-adopted girl who gets paired up with Homer just because of their ages. Her name was supposed to be Melody but a nurse made a typo on her records…which I actually find deeply relatable, because there were several birth certificate errors on my dad’s side of the family that led to people being called different names than were intended. My dad found out in his sixties that the middle name he’d been using his entire life wasn’t the middle name on his birth certificate (and if that seems like a long story…it is, and you kind of have to know my dad’s family for it to make sense). All I’m saying is…it happens.

-Melony is presented as a) large and b) hypersexual. A favorite character type for male novelists of a certain age! There’s a pretty horrifying scene (that I can’t figure out how to describe here in the words I allow myself to use in this newsletter) where she finds an old photograph that, hmmm…depicts bestiality, I guess is the best way to put it. It’s actually a big part of the plot and it’s one of those classic John Irving scenes that’s gonna haunt you forever!

-A young, well-to-do couple comes to St. Cloud’s—Candy Kendall and Wally Worthington. Candy’s getting an abortion because she’s not ready to get married, and they show up at St. Cloud’s during a time of chaos that’s presented as slapstick (multiple dead bodies lying around). They hit if off with Homer and offer to take him with them for a couple of days, and Dr. Larch jumps at the chance, despite the fact that it’s breaking his heart because he loves Homer like a son, even though he’s never said it.

The relationship between Dr. Larch and Homer is, hands down, the best and most moving part of the book so far. Dr. Larch is, for all intents and purposes, Homer’s dad, and they’re having the typical father-son disagreements. Namely, Homer doesn’t want to perform abortions and he maybe doesn’t even want to be a doctor.

As Nurse Angela puts it, “a kind of stubborn goading had developed between Dr. Larch and Homer Wells that [she] had never expected to see existing between two people who so clearly loved and needed each other.” In other words, they have a very normal teenager/parent relationship.

And then, just before Homer goes off with Candy and Wally, they gruffly (and while Dr. Larch has a body on the table cracked open with its literal brain stem exposed) exchange I love yous. Male emotions! You love to see them.

So here we are at the end of chapter five: Homer is off on a new adventure, Melony is pissed off, Dr. Larch is sad, Candy and Wally are presumably about to face some challenges, war is looming, and I’m freaking out over how much I love this book!

And this is only a fraction of what happened in these first 200-some pages. What did you think? Here are some questions in my mind:

-Is Dr. Larch’s ether habit gonna catch up to him?

-Is Melony going to hurt someone and/or destroy a copy of Jane Eyre?

-What’s going to happen with Candy and Wally?

-What will St. Cloud’s do without Homer??

-How is Homer going to function in the world? He’s basically a baby deer, wobbling around on unsteady legs.

Seriously, I’m dying to know what you think. I’m sorry I chose a readalong that’s so medically-focused—I mean, I’ve been through childbirth so I wouldn’t consider myself super squeamish, but there are still a lot of body details in here that sometimes make me uneasy.

I’ll be back next week (1/29, barring any more unexpected days off school) for chapters 6-8. Please forgive any typos. See you soon. xo

It’s a short and extremely informative episode! Highly recommend!

I remember the first time I read this I was on a lunch break and took out - yeah that was a mistake! No eating while reading Irving.

I know I'm late to the party, but better late than never, eh? I'm absolutely loving this book. I haven't read Irving since A Prayer for Owen Meany for a high school class (which I also loved, so I'm not really sure why it has taken me this long to pick up another Irving?!) The voice, the tone, the RANGE of this book! Also, re: the Photograph, et al, will absolutely haunt me forever. As will the whole gonorrhea thing 🥴 Really there's a lot of horrifying elements, but they're somehow softened with heart and humor? (The range!) Looking forward to reading part 2 (both Irving and your recap 😁)